adapted from the Bible study “Job” by Eric Ortlund.

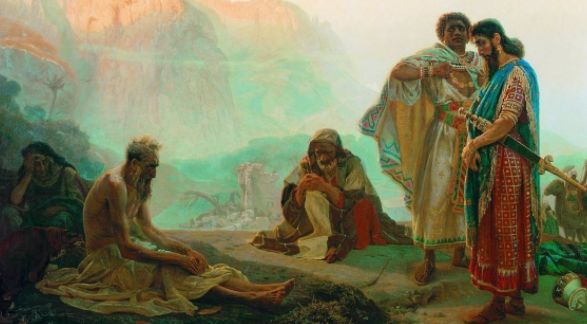

It can be easy to think of Job as a

book you turn to if some unexpected tragedy happens, but can otherwise be safely

ignored. Perhaps the most important reason for reading the book, however, is

that Job’s tragedy — an experience of searing pain and loss which did not make

sense within any framework Job had — is all too common.

My experience in

teaching the book in academic and pastoral settings is that almost everyone in

the room knows someone who has undergone a Job-like experience — or they are

suffering one themselves. It seems to be not a question of “if,” but “when” God

will allow some tragedy too painful to be borne quietly, and we, like Job, will

wonder why God would repay imperfect but sincere service and friendship in this

way.

Learn to Interpret

Suffering

A related reason for studying the book is that it widens our

ability to interpret suffering. Biblically, sometimes God allows pain because of

sin (as in Ps. 38) or to grow us spiritually: suffering produces character, and

character endurance (Rom. 5:3). True as these are, neither can explain Job’s

ordeal: not even the Accuser could find some sin which would prompt God’s

punishment (Job 1)!

And Job is presented as a mature believer — although

he had to confess sins (31:33–34), the description of his spiritual integrity in

1:1 uses biblical terms to describe settled maturity. Further, the book never

resolves Job’s suffering by pointing to some spiritual growth on his part.

Rather, Job’s agony ends only in a deeper vision of God (42:5). This is helpful:

the book is teaching us that painful loss can become an avenue for God himself

to reveal himself and draw close in a way he never has before.

A third reason for reading Job is

found in the first chapter: “Does Job fear God for nothing?” (1:9). The Accuser

argues Job doesn’t really love God for God’s sake, but only because of secondary

benefits which accrue in the relationship (the blessings of 1:1-4). Once those

benefits are gone, Job will show how he really feels about God — so the Accuser

claims.

This creates the deep drama of the book’s early chapters: will

Job hang on to his relationship with God when he has every earthly reason to

give up on him? It creates drama for the Christian reader, as well, because all

of us benefit from our relationship with God in ways different from the central

benefits of the gospel: forgiveness of sins and eternal life. If you had to go

to the funeral of one of your children on a Saturday, would your worship the

next Sunday be just as enthusiastic? God is worthy of that level of devotion —

but would we show it?

The author’s purpose in raising this question is

not to shame us, but to help us understand why God allows inexplicable

suffering. In chapters 1–2, Job proves the genuineness of his love for God: Job

has no ulterior motives and treats God as his own reward. The same opportunity

is given to us to tearfully but sincerely affirm that we have no treasure on

earth more precious than God (Ps. 73:25). And a faith of that quality is the

only kind of faith which will save you.

Finally, Job should be studied because

it gives tremendous hope and encouragement in suffering and nourishes endurance

in the midst of it. The Lord’s answer to Job in chapters 38–41, far from blaming

him as his “friends” did, paints a picture which is realistic about what is

still unredeemed about the world, but shows the tremendous joy God takes in his

world without ignoring what is wrong with it.

But the Lord does not leave

Job there: the final speeches about Behemoth and Leviathan speak of a coming

defeat of a great supernatural enemy when God scours all evil from his creation,

and the former things pass away. The poetry of these chapters foster the same

vision and hope in Christians who know without understanding

why.

[written by Eric Ortlund, an associate professor of Old

Testament]